An Injustice?

Why "Redeeming Justice" Deserves Recognition On The New York Times Bestseller List

A few years ago on a hot summer day, I decided to take public transit home from downtown Denver. During the course of the ride, the person seated next to me and I struck up a conversation. A Black gentleman appearing to be in his seventies, he shared with me a lot of deep wisdom and insights about life during our brief encounter.

Realizing that my ride stop was imminent, I hurriedly asked him one final question that had me curious. “What would you say has been your greatest achievement in life,” Just as he was preparing for his stop, he looked at me with raised eyebrows and responded “not having gone to prison.” Needless to say, I was absolutely stunned.

It’s a well-documented fact that Black men are incarcerated at unprecedented rates in the U.S. In fact, according to the data-gathering site Statistica, the incarceration rate among African Americans was 465 incarcerations per 100,000 of the population, the highest rate of any ethnicity in the nation.

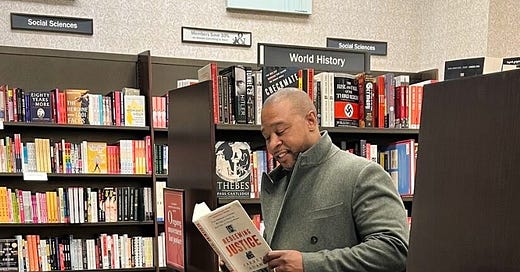

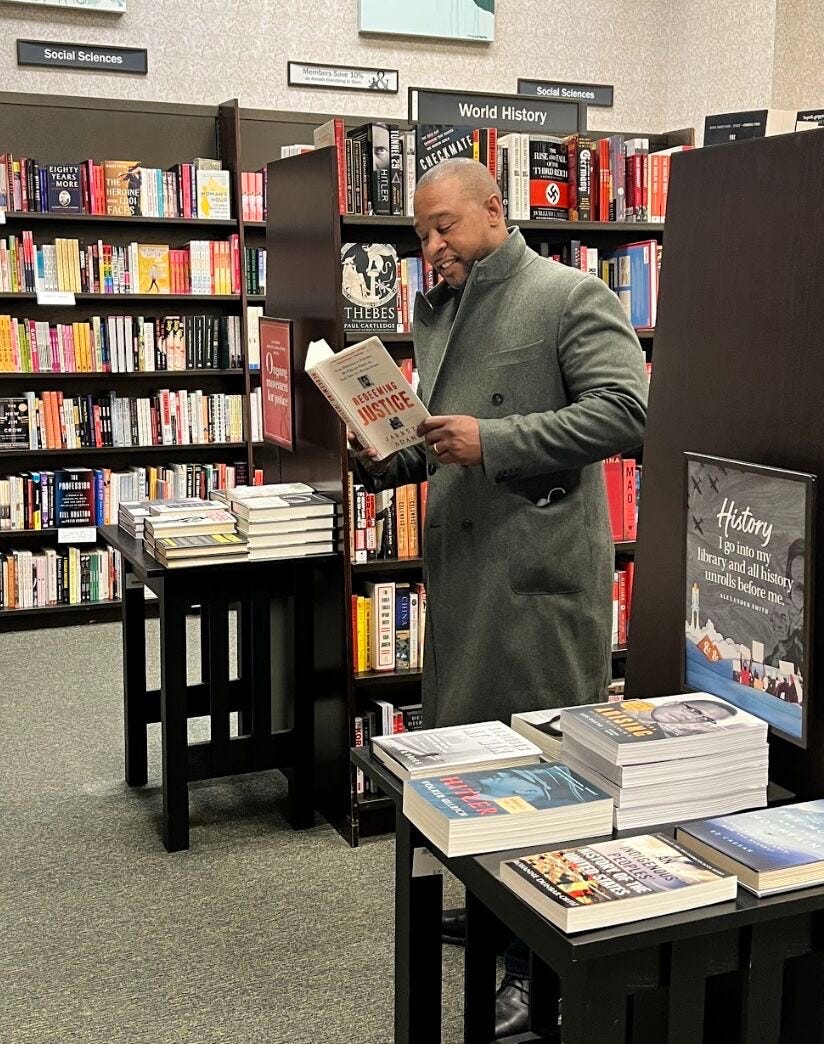

A couple of months ago I was introduced to the book “Redeeming Justice: From Defendant to Defender, My Fight for Equity on Both Sides of a Broken System,” written by criminal defense attorney Jarrett Adams. Having read over 1,000 books in my lifetime, I’m now inclined to rank it among my top three ever.

As the book’s powerful narrative uncovers, Adams at seventeen years old found himself facing a nearly three decades sentence behind bars. As he notes:

“In 1998, I was falsely accused and ultimately wrongly convicted of rape. I was sentenced to prison for twenty-eight years. I, too, had done nothing. I, too, got terrible legal advice. Unlike my clients, I made a catastrophic mistake that set the whole thing in motion, putting me on the path I’m on today. I went to a party. Three of us—three Black kids from Chicago—drove to a college campus in Wisconsin. At the party, we each had a consensual sexual encounter with the same girl, a white girl. Her roommate walked in, called her a slut, and stormed out. These were the facts. But the girl later said we raped her.”

Adams' book offers a sobering account of his incarceration experience and the profound impact that it had on his life as well as his family. In one of the book’s many powerful excerpts, he describes how his cellmate in the Wisconsin prison where he was housed played a pivotal role in decision to fight his eventual release

“You’re in here for some racist crap. Period. No evidence at all.” The is a “guy out there, playing basketball with you (in the prison yard) serving ten years for murder. You pulled twenty-eight for this?” …..“You are not taking this seriously. You have a case. Listen to me—”

Hearing this, Adams was prompted to spend every available hour he was permitted outside of his cell researching his own case in the prison law library. He also began providing informal representation for other inmates who found themselves facing petty charges in the prison system. Here, in many respects, he was planting the seed for his eventual decision to attend law school and become a defense lawyer.

While behind bars — nearly 10 years total — Adams relentlessly educated himself on the prevailing judicial system and the laws undergirding it. He sent voluminous amounts of letters to authorities, attorneys, and the Wisconsin Innocence Project asserting his innocence.

With the unrelenting support and prayers of his mother and aunts, Adams became obsessed with the U.S. legal system and all of its flaws. After discovering that his constitutional rights to effective legal representation had been violated, he reached out to the Wisconsin Innocence Project, an organization that helps exonerate the wrongfully convicted. This led to his eventual release after nearly ten years in prison.

Exonerated in late 2006, Adams in the book offered an account of his release process in the book that left me shaking my head:

“The sheriff, court order in hand, waits for me at the threshold of a doorway inside Waupun Correctional Institution. By law, the prison has to deliver me to him. He can’t cross the threshold. As the sheriff waits, a guard comes into my cell, chains me up, and puts me in shackles. Another nonsensical protocol.

I come to (the prison warden) Captain Belinsky at the front desk. He twirls his mustache with his cigarette-stained fingers. He coughs and snaps at me. “What’s your number?” I stand as straight as I can, the shackles biting into me. “370583.” “That’s not your number. You trying to be a smart guy?” “Oh, no, sir. I’m giving you my number backward because I’m giving it back to you. I don’t need it anymore.” He curses under his breath. The sheriff looks at me, and gestures at my shackles. “What is this? Why is he all chained up?

“That’s how we do it,” Belinsky says. “Take all that off. Handcuffs will do.” Belinsky sniffs. “He could make a run for it.” “I kind of doubt that a guy who’s about to get out is going to try to break out,” the sheriff says.

After his release, Adams went on to earn a law degree from Loyola University of Chicago, Adams to a position with the New York Innocence Project, giving him the distinction of becoming the first exoneree ever hired on the legal staff by the nonprofit. In his inaugural case, he argued before the same court where he had been convicted a decade earlier—and won.

Today, through his own law practice, Jarrett Adams has one mission: To apply the legal expertise and life-changing experiences of its founding partner, Jarrett Adams, Esquire, to protect the Constitutionally guaranteed rights of an individual throughout the legal process.

Redeeming Justice is a riveting story of hard work, persistence, and full-circle redemption. Adams draws upon his own personal experiences in the judicial system to expose the racist tactics used to convict and incarcerate young men of color who often lack the legal representation and financial resources to get a fair trial.

In my opinion, Adam’s book deserves New York Times bestseller recognition. It would be an injustice for this not to occur.

_____________