The South has always lived in my bones—even if I never personally lives in a Southern State

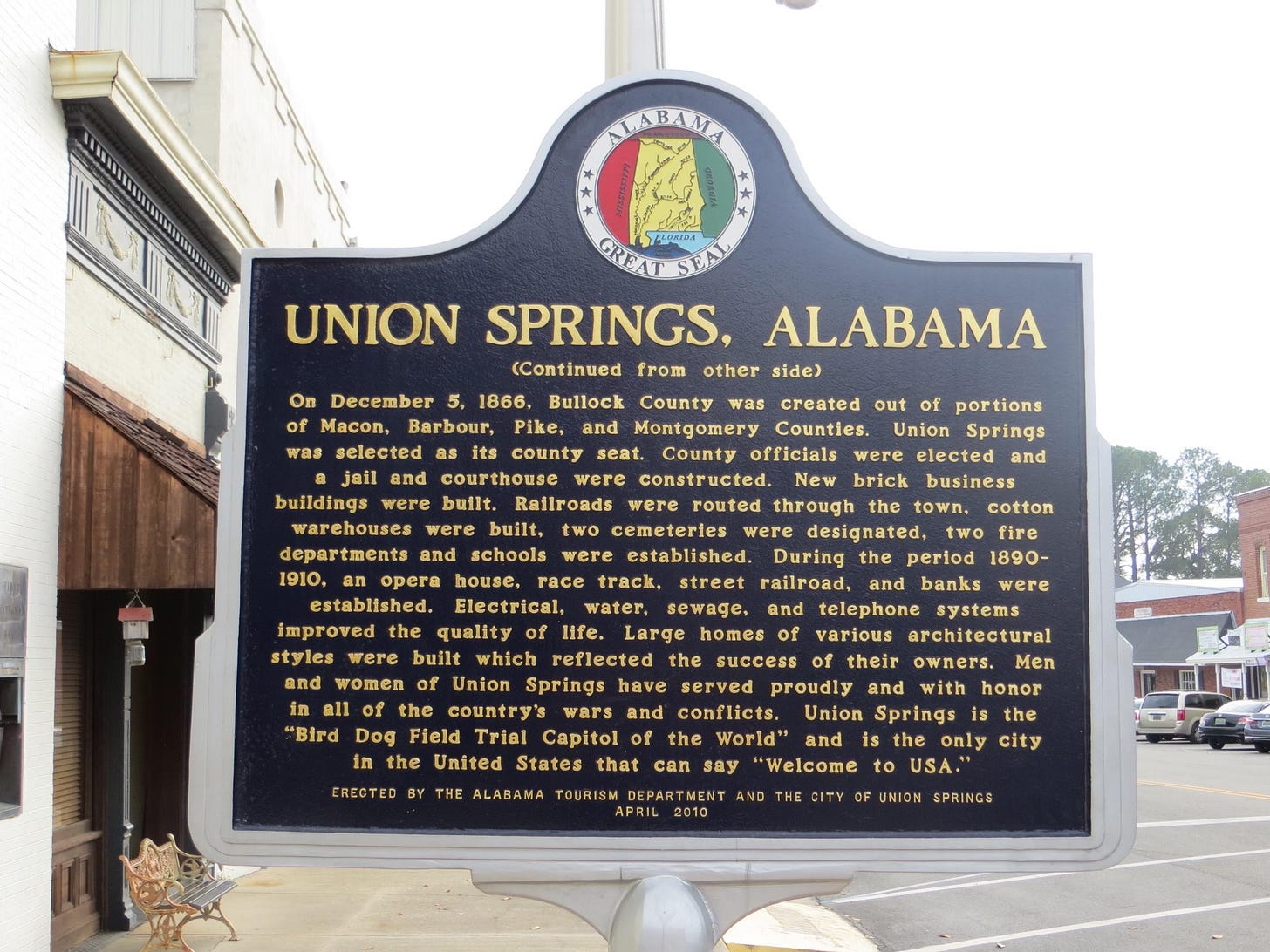

My father was born in Union Springs, Alabama, a place where the red clay runs thick with memory. My mother hailed from Richmond, Virginia, a city where cobblestones still echo the footsteps of both rebellion and resistance.

On both sides of my lineage, the South is not just a backdrop—it’s an origin story. Their migration northward didn’t erase the imprint of the South on our family. It merely relocated it.

Holidays, habits, speech rhythms, religious customs, and stories soaked in sweet tea and sorrow kept the region alive in our household. That deep familial connection sparked a hunger in me to understand the South not as myth or stereotype—but as lived experience.

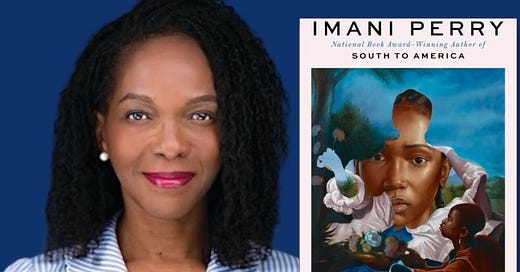

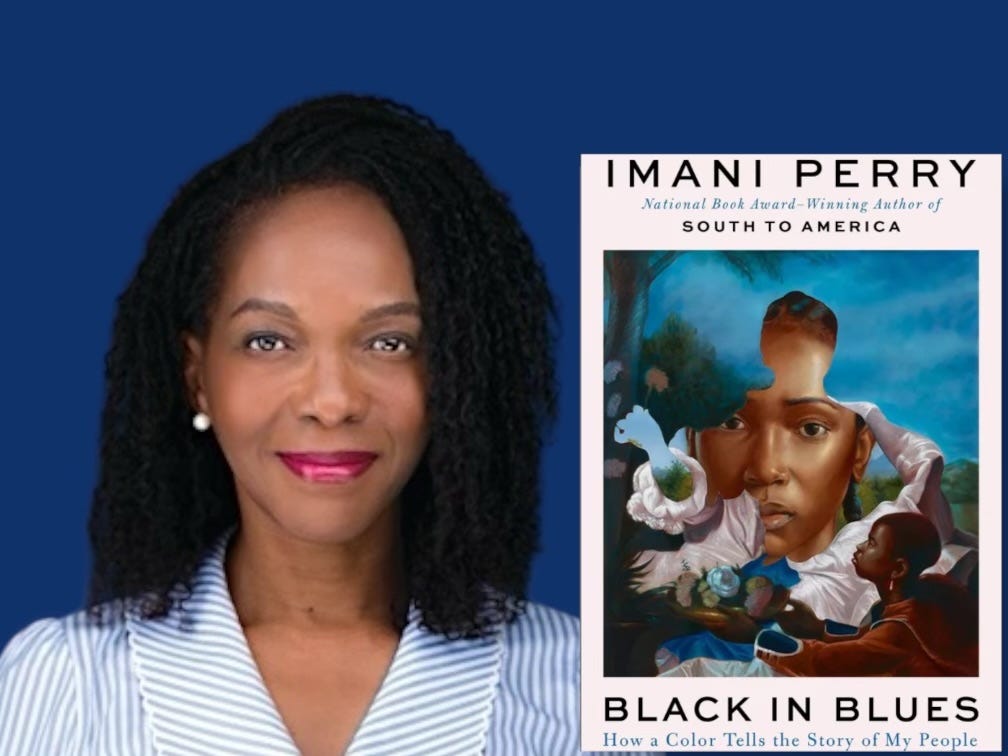

It’s that desire that led me to Imani Perry’s South to America and Black in Blues—two books that feel less like intellectual texts and more like spiritual reclamations.

Reading Perry is like watching someone perform a musical riff on history—fluid, soulful, unpredictable, but unmistakably grounded in tradition. She doesn’t offer the South as a caricature or a monolith, but as a living, breathing paradox.

In South to America, Perry makes the bold argument that the South is not just part of America—it is the beating, bruised, and beautiful heart of it. And if we want to understand this country in all its complexity—racially, economically, spiritually—we have to understand the South on its own terms.

For me, Perry’s writing offered a mirror. As she moved through New Orleans, Appalachia, Georgia, and her native Alabama, I felt echoes of my own ancestral roots. She doesn’t merely tour the region—she communes with it.

Her prose glides between historical insight and personal reflection, illuminating how the South is both a site of trauma and of tremendous transcendence. It’s a place where unspeakable violence and unshakable faith have always lived side by side.

And then there’s her newest book Black in Blues—a book so unique in its structure and soul that it defies genre. Through the color blue, Perry offers us an emotional cartography of Black life.

Indigo dye traded for flesh. The melancholy of the blues. Blue police uniforms and blue bottle trees. The sea that swallowed so many of our ancestors. Blue, in Perry’s hands, becomes a living witness—a silent scream, a sacred balm, a story told in hues both haunting and holy.

I remember the moment she described the periwinkle flower, often planted over unmarked slave graves. How many times have we walked by the sacred, unaware? That line alone stopped me cold.

Perry doesn’t just recount history—she feels it. And in inviting us to feel it with her, she does something rare in nonfiction, namely, transform the reader into a participant in the sacred act of remembrance.

Both books struck deep chords for me—chords I hadn’t fully heard before. I found myself thinking about how my father rarely spoke of Alabama, and how my mother often tempered stories of Richmond with caution.

Perhaps they were protecting me from pain. But perhaps, too, they were unsure how to name the contradictions that Perry so elegantly reveals. The South, after all, gave us both the whip and the spiritual, the auction block and the altar.

Perry doesn’t let us off the hook with tidy conclusions or polished narratives. She calls us into the messy, uncomfortable, beautiful work of sitting with the South’s complexity.

She forces us to ask, “how do we live with a past that still pulses in the present? And how do we honor the ancestors without romanticizing the soil that broke them”?

The house in Richmond, Virginia where my mother was raised

Today, as the South remains a hotbed of cultural, racial, and political reckoning, Perry’s work feels not only urgent—but prophetic. She shows us that this region is not locked in the past. It’s still unfolding, still evolving.

And whether we live there or not, we are all implicated in what the South has been—and what it will become.

So I leave you with this to ponder…..

What parts of your own story are rooted in places you’ve never fully explored?

What myths about the South have you inherited, and what truths are waiting to be uncovered?

How can you begin to see the South not just as geography, but as soul terrain?

And finally—what would happen if we all stopped running from the South, and instead, started listening to it?

Imani Perry’s work doesn’t just speak to the intellect—it speaks to the spirit. And through her words, I have come to see my family’s Southern story not as a quiet footnote—but as part of America’s unfinished symphony.

If you are finding “Great Books, Great Minds” to be a valuable resource in your polymathic reading journey, then we invite you to join us as a paid member supporter. Or feel free to tip me some coffeehouse love (dirty chai’s are my jam) here if you feel so inclined.

Your contributions are appreciated!

Every bit counts as I strive to deliver high quality feature articles into your inbox on a regular basis. Never any paywalls, just the opportunity to foster community, connection, and conversation one book at a time.

We will have to chat soon. In a “small world connection,” my family is from Union Springs, AL too. My maternal great-grandmother was born there in 1896. Her maiden name is was Coleman. She married a man from Bullock County, AL before they migrated to Chicago. His last name was Tellis.