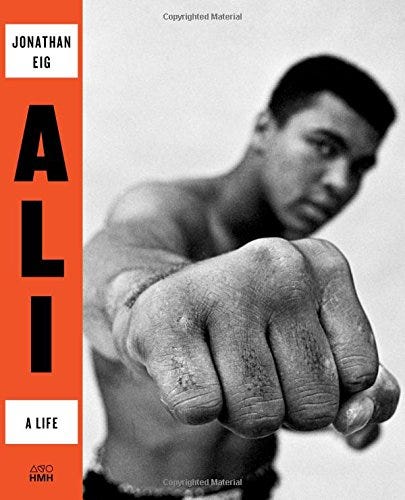

Bringing An “Ali” Punch To Racial Justice

Last year, I purchased this book at The Book Catapult during a stroll in San Diego’s South Park neighborhood. A robust 661 pages, it was encyclopedic in size. So much so that I eventually decided to purchase a digital version in order to not have to lug it around.

Ali: A Life was an intoxicating read for sure. It offered not only a deep dive into Ali’s life, but the racial context behind a world he had to skillfully navigate as a black man.

He was known as Cassius Clay until he accepted the name Muhammad Ali upon joining the Nation of Islam. As the author notes in the book:

“Cassius Clay would fall under the spell of two great influences in his life: The first was boxing, which was violent at its core but offered the promise of fame, riches, and glory. The second was the philosophy of Elijah Muhammad, who said a black man should take pride in his color, and that black men would soon rule the world, that they would use violence if necessary to come to power, and that there was nothing white America could do about it.”

On the eve of this groundbreaking week of protests and America coming together in solidarity to heal its racial past, I thought I’d offer some commentary based on a few excerpts from Ali: A Life.

—

“Clay is tall and stunningly handsome, with an irresistible smile. He’s a force of gravity, quickly pulling people into his orbit. Horns honk. Cars on Collins Avenue stop. Women lean out of hotel windows and shout his name. Men in shorts and girls in tight pants gather around to see the boastful boxer they’ve been hearing so much about. “Float like a butterfly! Sting like a bee!” he yells. “Rumble, young man, rumble! Ahhhh!”

I recall as a young kid growing up in Columbus, Ohio, being emboldened by Ali’s confident style. Whether in the boxing ring or being interviewed by Howard Cosell on Wide World of Sports, I found myself struck by his presence and confidence.

My own Dad, in an attempt to build my self-esteem, made me chant the oft-repeated signature phrase of Ali “I Am The Greatest.” Despite the negative views that some had about Ali’s braggadocious nature, Dad said, “bragging means that you’re confident.” As a young black kid, that was refreshing to hear.

“I am America,” Clay will proudly declare. “I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me.”

Ali was always swinging for racial equality and justice. And all of this began with constant reminders of his own self-worth.

“Much of Clay’s life will be spent in the throes of a social revolution, one he will help to propel, as black Americans force white Americans to rewrite the terms of citizenship. Clay will win fame as words and images travel more quickly around the globe, allowing individuals to be seen and heard as never before. People will sing songs and compose poems and make movies and plays about him, telling the story of his life in a strange blend of truth and fiction rather than as a real mirror of the complicated and yearning soul who seemed to hide in plain sight.”

Clay fame emerged during a time of great social unrest in our nation, not unlike the times we’re currently facing. This background context informed his philosophy and views over the years allowing him to leverage his boxing career to make a difference in the world.

“Cash and Odessa were opposites in many ways. He was rambunctious; she was gentle. He was tall and lean; she was short and plump. He railed against the injustices of racial discrimination; she smiled and suffered quietly.”

This is in reference to Ali’s parents. I am always fascinated by the genetic lineage of people. How they are characterized. And in this case, how family informed Ali’s own life.

“Although the majority of Kentuckians sympathized with the Confederacy, Kentucky did not secede from the Union during the Civil War. No race riots or lynchings occurred in Louisville between 1865 and 1930. Unlike most of their southern counterparts, black Louisvillians had been granted the right to vote beginning in the 1870s and had never lost it. Louisville’s white civic leaders expressed frequent and seemingly genuine concern for the living conditions of their black neighbors and gave generously of their own money to support black causes. In return, of course, these white civic leaders, like the slave owners from whom some of them were descended, expected blacks to be passive and accept their second-class status without fuss or fury.”

Ali grew up in Louisville, Kentucky. Growing up in Columbus, Ohio, my Dad took my brother and me for frequent vacation trips to Louisville. I remember as a young kid being struck at all of the black folks whenever we would walk the downtown Louisville Mall. They all seemed so free.

“Beginning in 1958, Clay would make three trips to Chicago in three years. More than any other city, Chicago provided him a pathway not only to adulthood and big-city life but also to new complexities defined by race and its consequences. Chicago was not the Promised Land, not for Clay nor for new arrivals from the South who had come to the city on Lake Michigan expecting something better than they’d left behind. Wages and living conditions for black families were far from equal to those of white families. Blacks were still not welcome in many jobs, unions, clubs, and neighborhoods.”

My Dad’s family moved to Chicago by way of the Great Migration. I consider the “Windy City” to be my adopted hometown and am still struck by the racial and socio-economic complexities that burden the city to this day.

“When a Russian reporter pushed him, asking if it was true that Negroes couldn’t eat in the same restaurants as whites back in the States, Clay was honest. He said, yes, there were times when it was difficult for a black person to get a meal in an American restaurant, but that wasn’t the only indicator of a nation’s greatness. Life in America was still wonderful. After all, he said, “I ain’t fighting off alligators and living in a mud hut.”

Ali was blunt, at times crass in using his big mouth to get his message across.

“Elijah Muhammad’s philosophy offered a black man the possibility of dignity and power. It offered him a sense of self. And the white man’s approval was not required. “The mind is its own place,” says Lucifer in Milton’s Paradise Lost, “and in itself can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.” The black man didn’t have to remain in hell just because the white man relegated him to it, Muhammad said. He had the power to forge his own identity, to transform the conditions imposed upon him, and he needed no one’s permission, no Supreme Court order. He could do it through the power of his own thoughts, through his own might, his own actions.”

Elijah Muhammad was an early influence on Ali's conversion to the Nation of Islam. I would argue that NOI is the most prominent organization promoting black pride and self-empowerment that exists today.

“I never felt free until I gained the knowledge of myself and the history of our people. This taught me pride and gave me self-dignity”

Ali makes an important point that’s relevant for the times we’re in. Protest without an understanding of the historical context behind it is severely weakened in its impact. Examining past lessons and even failure is critical to our forward advancement as a nation.

“Later, a variation of the quote would be widely attributed to Ali: “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong.” It would be coupled with another quote, one that would appear on T-shirts and posters bearing Ali’s image, becoming one of the most powerful quotations ever attributed to an American athlete: “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.”

Ali was a conscientious objector, who displayed an act of moral defiance by refusing to go to war. He stood strong for what he believed in. As an inherently peaceful man, he was opposed to the killing of innocent people. He frequently denounced the lack of respect and racism American servicemen experienced after returning from previous wars. Ali was convicted of draft evasion and banned from boxing but was never sentenced to prison.

“Ali, meanwhile, had little to say about race and politics, except to point out that he hadn’t voted in the presidential election—and, in fact, that he had never voted in any election, local or national.”

“I haven’t voted in 10 years and don’t intend to, particularly as long as we have two-party dominance. Why should I when 99% of us are beholden to their own self interests versus the true will of the people they’re charged with representing. Politicians are full of empty promises for black people yet we still continue to drink the Kool-Ade.”

It certainly will be interesting to see how Ali’s view informs Black American voters in the November 2020 election.