George W Gibbs, Jr. and His Historic Trek to Antarctica

“Anchored this morning in the Bay of Whales, digging holes in the ice with picks and shovels. This was the only way of tying the ship up along the ice. . . . When the Bear came up to the ice close enough for me to get ashore, I was the first man aboard the ship to set foot in Little America and help tie her lines deep into the snow. I met Admiral Byrd; he shook my hand and welcomed me to Little America and for being the first Negro to set foot in Little America.” —George W. Gibbs Jr., January 14, 1940

Few are familiar with the name George W Gibbs, Jr, the first Black person to set foot on the continent of Antarctica. Having sailed on the infamous USS Bear from 1939 to 1941, Gibbs was a member of Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s III expedition to the South Pole, widely considered the first collaborative project in history between the United States military and a private exploratory team.

With his crowning achievement, Gibbs left an important mark on humanity, breaking down barriers for not only people of color but demonstrating the importance of a more human, environmentally sensitive world.

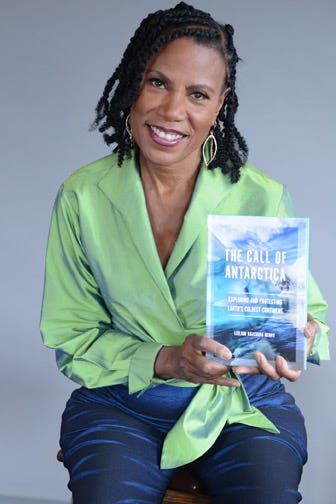

Now in a book entitled The Call of Antarctica: Exploring and Protecting Earth's Coldest Continent released on October 5th author Leilani Raahshida Henry offers a deep plunge into the historical legacy of her late father.

In the book’s forward, Ted Scambos, senior research scientist at the University of Colorado in Boulder and a veteran of twenty expeditions to Antarctica and the Southern Ocean to study the ice and the impacts of climate change offers a profoundly loving tribute to Gibbs and his contribution to the continent. He writes:

“This book is a brief introduction to the continent of Antarctica and its surrounding ocean, an overview of its history, and a sample of the science behind how the continent works. It touches upon Antarctica’s geology, biology, and environment. As a way of discovering more about the continent, we follow the story of a member of a past Antarctic expedition—the American George W. Gibbs Jr. In 1940, at twenty-three years of age, Gibbs was the first Black man to set foot on the continent.”

Scambos says that Gibbs experienced myriad inner and outer discoveries on his journey noting that he “had the adventure of his lifetime, and he embraced his role as a part of a diverse team.”

“He saw landscapes and wildlife that awed him. He felt the burn of racial discrimination, but he also knew interracial teamwork and harmony. He saw how other nations put less importance on skin color and more importance on fellowship. These experiences shaped him and set him on a course to become a civic leader and civil rights advocate in his state and nation. Above all, his example shows the power of outlook, attitude, and optimism. No matter the situation, Gibbs steered clear of resentment and focused on experiences and on being present. He appreciated every aspect of his journey, inward and outward, and spoke about the experience for the rest of his life. He felt the call of Antarctica.”

In a recent interview with “Great Books, Great Minds” author Leilani Henry shared pieces of her research and writing journey in unearthing her father’s story to the world. She says that while it’s a book about her father, the greater hope is that readers will walk away with a more in-depth understanding of Antarctica and its profound environmental importance to the world.

Henry had this to say when asked about her decision to write the book:

“Honestly, I was expecting my father to write the book. For many years, he had expressed this intent but kept delaying, saying that he was waiting for more information. And I never could understand why he needed more [Laughter] about his life. I mean, sure he was in his eighties so I get that he might need a memory jog. But his continual deflections made no sense. And then he passed away.”

According to Henry, before he passed away he had commissioned a journalist to help him. She was an editor at one of the local newspapers with who he had hit it off after she’d done a beautiful feature piece about his life and Antarctica. The two grew very close so he commissioned her to write the book.

Says Henry—

“After he passed away I went to her and said, ‘“thank you for agreeing to write my father’s story. Let’s do this. What else do you need, let’s do this. And she says, “well, I decided to start a family and so I’m not going to be able to write this book. While I sat stunned, she then proceeded to gather all of the stuff they had prepared in order to give back to me.”

Henry admitted that she was quite crushed at first before coming to the realization that this was a golden opportunity to step into her family’s legacy.

“At that point I felt it made sense for me to do this rather than having someone outside of the family, even though the person my father had commissioned was a close friend. So that is what actually sparked me to write the book.”

Over the course of her writing journey, Henry says that the book morphed several times as she tried to clarify the narrative and filled in all of the historical holes of her father’s quest. A big breakthrough, however, came when her mother found her father’s travel diaries behind the dresser after a residential move. Exclaimed Henry:

“That's when I realized that ‘OK, this is what he meant when he kept saying that he lost all of his materials and needed more information.’ So now I am in possession of two of his diaries.”

Asked about the contents of the diaries, Henry added this:

“In one of his diaries, he wrote every day for six months, chronicling his round trip from Boston to Antarctica and back. And then there was the second journal, where he didn’t write. It was about his trek from Philadelphia by way of New Zealand to Antarctica and then back to Philadelphia. So with all of this material, my first thought was to write a biography. And then I thought I would write about the expedition because there wasn’t anything out there about that event.”

In terms of whether she had visited Antarctica in an attempt to retrace some of her father’s steps, Henry had this to say:

“I have been and that was one of the things that helped me finish the book after having stopped and started it many times.”

She admits that writing the book was one of the hardest things she has ever achieved in her life:

“Honestly, writing the book was so, so very hard. But despite how challenging it was, I discovered on that trip that I had a deep desire to complete it as I really did care deeply about the project. Moreover, I fell in love with Antarctica which was really cool.”

Henry says that one of the biggest discoveries she encountered while completing the book was the deep connection between the people who were on the ship her father was on.

“Over time, I started realizing that the people on the ship had built lifelong relationships and connections between them. And those who didn’t have a lifelong relationship with Antarctica. Many of them, in fact, had passed on their experiences to their descendants. So I went and I met with or communicated with a number of them along with some of the very people that were on the ship.”

In concluding our conversation, she shared her greatest hope in terms of what readers of the book walk away with:

“I hope that they are excited about the message around what it will take to protect Antarctica. I also hope that it will inspire scientists of color who are interested in polar science or find encouragement in seeing that as a career.”