How Black Folks Are Cast

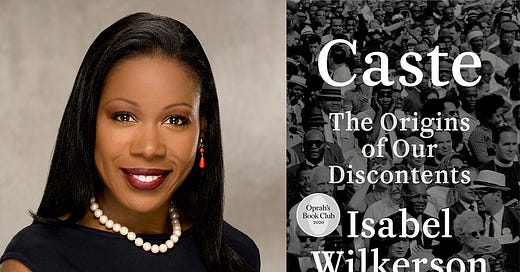

“Color is a fact. Race is a social construct," says Isabel Wilkerson, author of Caste: The Origin of Our Discontents

As was the case with many Black Americans, George Floyd’s murder was a triggering experience. Once again, it exposed the ugly stain of racial injustice, the aftermath of which led me to conclude that racism in this country is exponentially worse than I could have ever imagined in my wildest dreams.

The recent shooting in Buffalo, New York serves as still another reminder of the historical legacy of racism in America. For me, it raises deeper questions about why something such as the color of a person’s skin color can evoke such an evil response.

The pervasiveness of this issue has led me to take a dive into the recesses of Black history to unearth some deeper perspectives on this theme. I have found this journey to be a mind-blowing experience.

Among the compendium of books I’ve turned to for answers is “Caste: The Origin of Our Discontent” by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson. This follows my reading of her first book “Warmth of Other Suns,” which I credit with radically altering my understanding of America’s racial history. It is one of my top five favorite reads ever.

Caste is a profound achievement of scholarship and inquiry in its own right, replete with its profoundly moving storytelling and exegesis-rich analysis.

According to Wilkerson, Caste can be best defined as:

“…granting or withholding of respect, status, honor, attention, privileges, resources, benefit of the doubt, and human kindness to someone on the basis of their perceived rank or standing in the hierarchy." Racism and casteism do overlap, she writes, noting that "what some people call racism could be seen as merely one manifestation of the degree to which we have internalized the larger American caste system."

Using this backdrop in the book, Wilkerson connects the dots between American Blacks, which she refers to as “America’s untouchables” and those in India's lowest cast, known as the Dalits.

Her predominant thesis? While race is a global phenomenon, it has seen its most violent manifestation in the form of oppression, marginalization, and violence among Black people in America. She asserts that whites in America represent the dominant, highest caste, on par with the Indian Brahmins.

Chapter 6 entitled “The Measure of Humanity” is where Wilkerson began excavating the important historical and scientific context of this racial contract. She writes:

“Geneticists and anthropologists have long seen race as a man-made invention with no basis in science or biology….

“As a window into the random nature of these categories, the use of the term Caucasian to label people descended from Europe is a relatively new and arbitrary practice in human history. The word was not passed down from the ancients but rather sprang from the mind of a German professor of medicine, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, in 1795. Blumenbach spent decades studying and measuring human skulls—the foreheads, the jawbones, the eye sockets—in an attempt to classify the varieties of humankind.”

It’s here where Wilkerson reveals that Blumenbach is thought to be the first person to coin the term Caucasian, “on the basis of a favorite skull of his that had come into his possession from the Caucasus Mountains of Russia.”

Citing the prominent geneticist J. Craig Venter, she notes that two decades ago, “analysis of the human genome established that all human beings are 99.9 percent the same.”

“Race is a social concept, not a scientific one,” said J. Craig Venter, the geneticist who ran Celera Genomics when the mapping was completed in 2000. “We all evolved in the last 100,000 years from the small number of tribes that migrated out of Africa and colonized the world.”

What all of this suggests, according to Wilkerson, is that the racial caste system that has been erected in America, the driver of hatred and civil unrest, was erected on what anthropologist Ashley Montagu calls “an arbitrary and superficial selection of traits,” taken from a small selection of genes that make up humans. As the book notes:

“The idea of race was, in fact, the deliberate creation of an exploiting class seeking to maintain and defend its privileges against what was profitably regarded as an inferior caste.”

Adds Wilkerson:

“Small children who have yet to learn the rules will describe people as they see them, not by the political designations of black, white, Asian, or Latino, until adults “correct” them to use the proper caste designations to make the irrational sound reasoned. Color is a fact. Race is a social construct.”

In reading this, I was reminded of a doctor's visit with my daughter years ago when she was five or six. While in the waiting room, I filled out the infamous “health assessment” form on her behalf for her first visit. At the very end of the last sheet, a question appeared about race and ethnicity. Curious, I asked what her response would be to the question (she’s bi-racial). Visibly upset, she says to me “Daddy, none of these really fit.”

I recall golfer Tiger Woods when confronted with a similar question on the Oprah Winfrey show, describing himself as “Cablinasian,” a self-created word he says best reflects his background as a blend of Caucasian, black, Indian, and Asian.

Then there’s the stunning revelation in the months following the high profile, racially charged arrest of prominent Harvard Black History professor Henry Louis Gates by a white police officer that the two were related.

Wilkerson goes on to say in her book that people often deflect accusations of racism, with remarks like, “I don’t have a racist bone in my body,” or “I’m the least racist person you could ever meet.” Or my personal favorite, “I have a best friend who is Black.”

In my opinion, people who unconsciously say that they don’t see color have nevertheless convinced themselves on a conscious level that this is true. Wilkerson offers this in terms of a response:

“Rather than deploying racism as an either/or accusation against an individual, it may be more constructive to focus on derogatory actions that harm a less powerful group rather than on what is commonly seen as an easily deniable, impossible-to-measure attribute”

In a statement that seemed to bring it all home for me about the historic legacy of Caste, Wilkerson in her book adds:

“It’s insidious and therefore powerful because it is not hatred, it is not necessarily personal. It is the worn grooves of comforting routines and unthinking expectations, patterns of a social order that have been in place for so long that it looks like the natural order of things.”