How To Live Like A “Monk”

For my entire existence, I’ve had a rebellious streak. My Mom’s maxim that “those who succeed dare to be different” was deeply infused into my DNA at a very early age.

This contrarian nature of mine has led me on a circuitous path, one that is foreign to those clamoring for a stable and idyllic lifestyle. It has been both exhilarating and exhausting. I wouldn’t change it for anything.

My first awareness of the propensity I had to steer clear of what others considered to be normal was in Catholic grade school where my stubborn refusal to hold a pencil correctly subjected me to the ire of teachers. Despite having never conformed, I still possess the most stylish cursive writing that you’ll ever find on the planet.

Finding Resonance In Monkhood

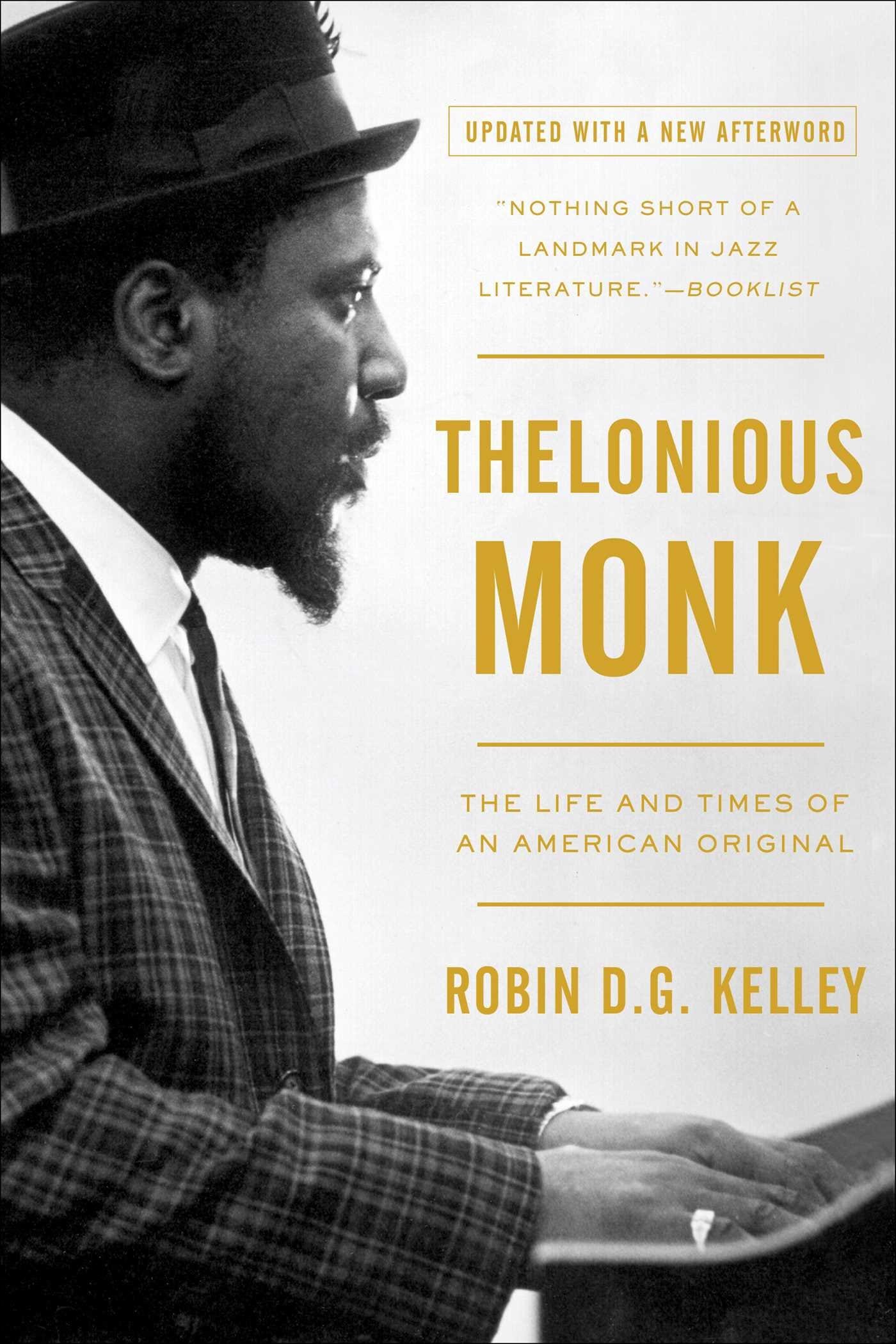

As a contrarian jazz enthusiast, I have long resonated with the music of legendary jazz pianist and composer Thelonious Monk. But I knew little about his own rebellious streak until reading Robin Kelley’s great book entitled “Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original ” Kelley, professor of history at UCLA, considers Monk the "most innovative, if not the greatest composer in the music we call jazz."

In the book, Kelley does a thoughtful exegesis into Monk’s mystique through interviews with his closest friends and family, his private papers, and audio files of Monk himself. He unearths the proclivities and character traits of Monk that made him uniquely different in the musical world.

Few knew about Monk’s life until Kelley’s book, a rich trove of meticulous research laced with access to his family. He does a deep dive into the assertions that Monk was an idiot savant instead view him as a man full of deep complexities who struggled with mental illness. Despite portrayals to the contrary, it reveals Monk’s fully engaged love for both his family and music.

Born in 1917 in Rocky Mount, N.C., Monk and his family moved when he was 5 to New York. An autodidact, he taught himself to read music and began playing the piano a year later. Known for his unique improvisational and spontaneous style, he created a robust collection of musical albums over the years including my favorite, Round Midnight.

Monk’s emergence came during the period of bebop in 1940, where the jazz emphasis shifted from big bands to smaller virtuosic themed groups. Refusing to conform to common convention, Monk employed a four-finger typing style where he often flattened his fingers while playing, utilizing his elbows and forearms to exact the sounds that he wanted. His music favored slower, more paced tempos and highly complex rhythms and melodies

Reclusive, Monk rarely granted interviews and shied away from speaking to his audiences. Known for his signature goatee, smoked sunglasses, and fancy hats, Monk carved his own quintessentially unique brand statement.

Big footed, he rhythmically tapped his feet while at the piano while playing. And whenever one of his musical trios did a solo, he often arose from his piano stool and danced in circles like a stoic whirling dervish.

Despite all of his success, a silent bitterness held sway over much of Monk’s life. He was financially broke for most of his career and his musical license was revoked after an arrest during a pivotal time in his career.

In later years he found a fervent supporter in Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter who was a jazz enthusiast and part of the powerful Rothschild family — and a jazz enthusiast. She offered him money, provided him transportation to gigs, and allowed him to rehearse and do recording at her home.

Because of his acclaim, Monk had the distinction of being one of only five jazz musicians recognized on the front cover of Time Magazine along with other musical titans like Louis Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, Duke Ellington, and Wynton Marsalis.

In the early eighties, his mental and physical health took a downward spiral. He ceased writing music and literally became a full-fledged recluse for nearly a decade. With his condition worsening, he resided as a guest at de Koenigswarter’s mansion in New Jersey where he passed away from a stroke in 1982. He was 64 years old.

Kelley’s book offers a fascinating portrait of Monk’s uncommon talents and creative genius. But more than anything, it highlights his unwillingness to be anything other than who he was at the core — eccentric, colorful, and true to his unique musical proclivities.