We all know the old saying, “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” But what is equally true is that you can only judge a book by what it covers – and more pertinently, by what you take away from it.

I have been thinking about this a lot as I have embarked on the latter part of my life journey, namely, the practice of reading books that make me feel uncomfortable.

As a result of having grown up in the 1950s and 1960s in an all-White culture, the books I now find myself gravitating to are Black history books.

I realize looking back that I came of age when most White Americans had little awareness of the depth and horror of Black oppression in our country, and the extraordinary triumphs of the Black community, often by ordinary people, that communicate universal lessons of resilience, faith, bravery and heroism.

Recently, I have read four powerful Black history books that made me -- a White Jewish American in my 70’s –- very uncomfortable.

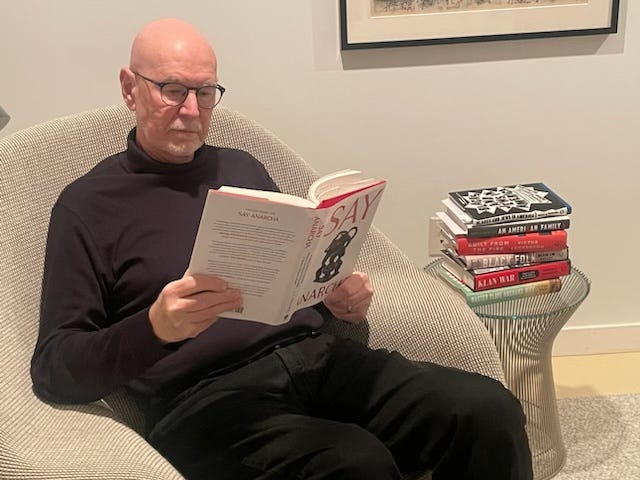

The first was Wilmington’s Lie by David Zucchino. This Pulitzer Prize winning book deals with the 1898 violent racial massacre staged by White Supremacists in Wilmington, North Carolina.

The second book that made me uncomfortable was Black Folk by Blair LM Kelley, which describes many instances of the mistreatment of Black people by Whites not only in the South but in the North.

The third book that made me squirm was Blacks and Jews In America by Terrence L. Johnson and Jacques Berlinerblau. This book consists of dialogues, essays and interviews about Black-Jewish relations starting with the slave trade in the 1600’s and continuing through 2022, the year of publication.

While technically not a “Black history” book, it shares many of the characteristics of Black history books. This book had a special resonance for me as an American Jew.

The fourth book is Say Anarcha by J.C Hallman. This book is about Dr. J. Marion Sims from Montgomery, Alabama, who is regarded as the “father of modern gynecology.” Recent research has revealed that Sims’s great medical claim was the result of several years of experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women, without their consent and without anesthesia.

Each of these books was deeply troubling. I found myself experiencing and embracing some of the harshest realities that I could imagine through the prism of a Black person, thanks to the considerable skill, detailed research, first-hand accounts and piercing narrative styles of these authors.

How could the country I was taught to love, a country that I thought was uniquely exceptional and humane, perpetrate and sanction such horrific acts of violence and injustice against our fellow citizens?

What did this sickness in American society stem from? Why wasn’t I taught more about it in the all-White school system I had attended? And if I had, how might my life and career path have been different?

According to a recent report by the American Library Association, there has been a significant increase in the number of attempts to ban books in schools and public libraries in the United States. In 2022 there was a 38% increase over 2021 in the number of attempts to ban books. In the first three-quarters of 2023, over 1900 library book titles were targeted for censorship.

The most frequently targeted books are those addressing race and race relations, sexuality and gender identity. These banned books include critically acclaimed titles, such as Maus by Art Spiegelman, The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson and Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds.

The reasons offered as justifications for banning books vary.

Most often books are banned because the objectors consider them to be age inappropriate. In other instances, objectors claim that their targeted books will make readers feel bad about themselves or uncomfortable, such as when White people read about Critical Race Theory or the sordid histories of race relations and racial massacres in Tulsa, Oklahoma and Wilmington, North Carolina, for example.

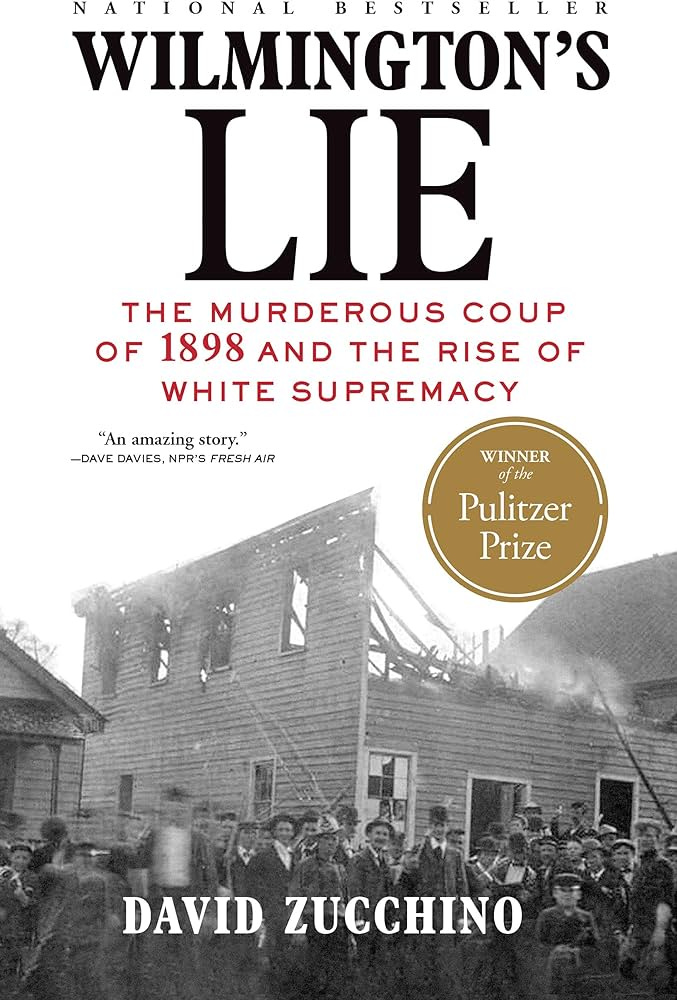

One continuing target for censorship is To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee, a 1960 Pulitzer Prize winner that focuses on race relations in the 1930’s in Macon County, Alabama, and which is sprinkled with the “N-word” and instances of abuses of Black people by Whites.

The stark reality is that in the U.S., books on Black history and other Black-related books are not “feel good” experiences for Whites seeking a better understanding of the Black experience in our country. As I have been pondering the importance of literary discomfort, I find myself thinking about a quote from the 20th century novelist Franz Kafka about the necessity to read books that make you uncomfortable. Kafka wrote,

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we're reading doesn't wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the ax for the frozen sea within us. That is my belief.”

I disagree with Kafka’s statement that we should “read only the kind of books that wound or stab us.” Rather, I believe we should read books for enjoyment, learning and self-help. These can help to improve and enrich our lives. But to grow, we must read books that “wake us up with a blow to the head” as the books described above did for me.

Just feeling “uncomfortable” with books you read is not enough. We should ask ourselves, “what actions am I taking as a result of reading uncomfortable books?” When I see expressions or acts of racism, am I speaking up? If I am witnessing an antisemitic incident, what am I doing to stop it? What can I do to help remedy the injustice I am observing?

In the years ahead I will search for books that will make me uncomfortable and that will cause me to examine and reexamine my own belief system. I am confident that each such book will contribute to my continuing growth.

Mr. Friedman spent 48 years as a trial lawyer. He is now an Executive Coach with MasterMethod (www.mastermethod.co). Mr. Friedman received a B.A degree in Philosophy from The Johns Hopkins University and a Juris Doctor degree from The George Washington University Law School.

Join Us Today and Support Independent Writing

As a supporting member of "Great Books, Great Minds," you'll dive deeper into a world where your book passions thrive. For just $6 a month or $60 a year, you unlock exclusive access to a close-knit community eager to explore groundbreaking reads.

You won't just take in a book; you'll engage in meaningful conversations, connect on a more profound level with fellow book lovers, and enjoy VIP discussions with bestselling authors.

Plus, you'll receive handpicked book recommendations tailored for you. This is your chance to be at the heart of a community where literature bridges souls and authors share their secrets, all thanks to your support.

In the spirit of community, connection, and conversation, please join us today. Always stay thirsty for a great book

Diamond-Michael

Independent Journalist and Global Book Ambassador

Wow, that Franz Kafka quote is mind-blowing. I tend to agree with Marc that there are other reasons to read as well that are equally important, but it's a tremendous justification for making sure our reading diet causes some dis-comfort, which is an essential ingredient in transformation.

Eloquent quotation from Kafka. I’d be sad for anyone who swallows it whole. I like books to lead readers to better selves and societies. Some do it, as Kafka suggests, like an axe to ice. Some do it by inspiration and delight.

Though I love history and deeply appreciate the work of historians, this post reminds me why I often reach for literature that gets both sensations in a single book - Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and Octavia Butler’s Kindred rank high on the list. Toni Morrison, of course. Many people would choose Beloved; I’d add Paradise, not quite so often read. The stories of Charles Chesnutt and Harriet Jacobs. And beyond the American experience, The Barefoot Woman by Scholastique Mukasonga belongs on this list. These and others draw me in to sympathy and hope even in the midst of devastation. I hold on to the resilience, resourcefulness, and love of individual characters to hope for a way through for all of us. Discomfort, yes, and also something else.