By Neale Orinick, Senior Contributing Writer

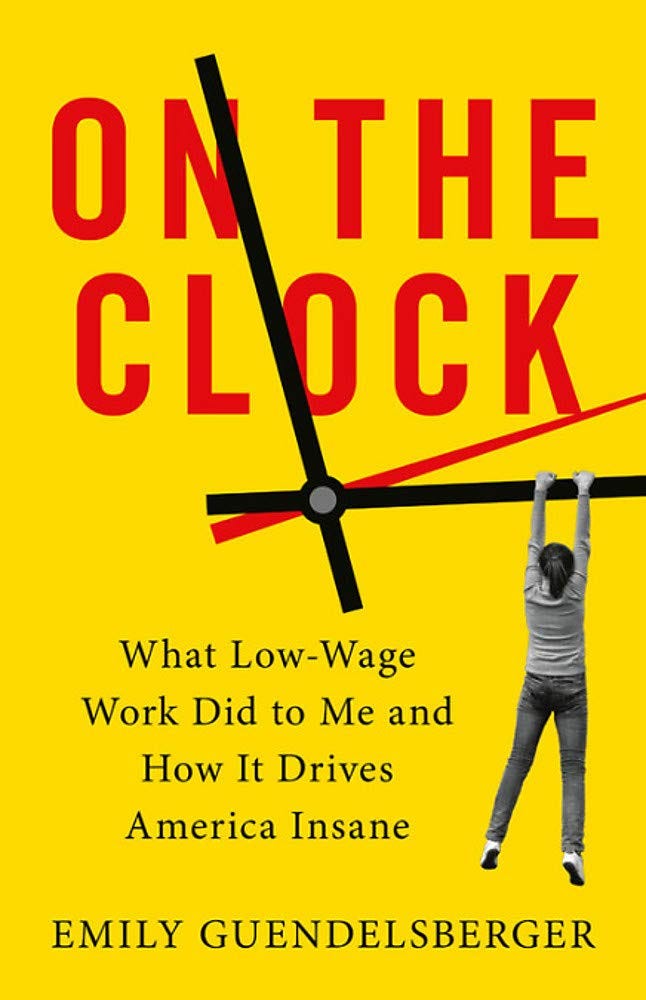

After finishing On the Clock by journalist Emily Guendelsberger I will never order a product from Amazon, talk to someone in a call center, or eat at McDonald’s again without thinking about this book. In fact, On The Clock should be required reading for all Americans to better understand the dehumanizing and debilitating affect the use of technology to increase efficiency and profits has on people.

Guendelsberg, a former editor for The Onion, found herself unemployed when the small-town newspaper she worked for shut down. She took the opportunity to research what the day-to-day experiences were like for low-wage workers in 2016 by going to work in an Amazon fulfillment center, call center, and at a McDonald’s. What she endured, observed, and recounts will resonate with those who have ever worked in those kinds of occupations (or still are) and make anyone in a white-collar “skilled” position rethink just how good they have it.

Amazon

The pain medication dispensing vending machine seemed odd when Guendelsberg first saw it as a new hire at an Amazon warehouse in Southern Indiana. By day three on the job she was desperately waving her employee ID at it trying to get some relief for her swollen, burning feet and legs that had given out on her earlier in the day.

Amazon fulfillment center employees work mainly in two positions, picking or packing. Guendelsberger chose to pick, figuring walking to get items was better than standing in place all day packing orders into boxes for shipping. She had prepared herself for lots of walking before applying, or so she thought. On an average day, Amazon pickers cover between 13 and 16 miles, bending and squatting to retrieve items from large drawers using an electronic scanner for nearly 11 hours a day.

Sounds simple, but the scanner is not just for finding items. It tracks your whereabouts at all times so the company knows when you are in the bathroom and for how long. It also counts down the seconds or minutes it takes you to find an item and beeps incessantly if you are taking longer than the time allotted to retrieve a particular item and rush off to get the next one.

One of Guendelsberg’s supervisors tells her, “there’s always an eye out there on you.”

“The ‘eye’ isn’t cameras-it’s the scanner gun former workers talked about, which wirelessly uploads your location and how long it’s been since your last bar-code scan in real-time. If you’re going too slow, the scanner will display a message telling you so. If you go too slow too often, a ‘coach’ will come to find you to tell you in person.”

By day three Guendelsberg is in so much pain from hiking the vast aisles of the fulfillment center retrieving items that, “my body mutinies.” She finds herself on the floor viewing her grotesquely swollen feet with horror and realizing she has already downed almost an entire bottle of pain medication with several hours left to go on her shift. Her scanner relentlessly beeps with increasing intensity to remind her that she is going too slow between scans.

Due to careful planning by Amazon, nobody finds her crying on the floor, nobody comes by to offer her a hand up. Isolation is intentional to keep people from chatting even briefly, thus slowing their productivity.

“Keeping us isolated makes logical sense because the alleys between shelves are so narrow. But it also eliminates the opportunity for inefficient workplace chatter, which I am convinced is a goal rather than a side effect.”

The author readily admits she expected some pain and fatigue, but not the soul-crushing agony of walking 15 or more miles a day doing hundreds of squats to retrieve items, day after day after day, most of it spent alone under duress to hurry at all times lest the scanner starts beeping ominously at you to move faster or risk being fired.

Despite the physical pain, boredom and isolation, she knows she has it easier than most of the co-workers she started with as a new hire (many of which vanish within a week or two). Most of the pickers she sees are past retirement age or parents of young children with an evening full of chores ahead of them before they can rest. She is flabbergasted by the heavily pregnant women picking and knows her heavy-duty supportive work shoes stick out when everybody else is wearing cheap old sneakers.

“Despite all my research I’m embarrassingly unprepared for what “normal” means outside of the white-collar world, and I have grossly misjudged what $10.50 an hour is worth to a lot of people. I expected the pain. I expected the monotony. I hadn’t expected so many people to regard this as a decent job.”

Until her time at Amazon, the author never realized that having your breaks timed to the second, working through pain and illness and constant monitoring would be normal to so many.

After another exhausting day, Guendelsberg is starving and anxious for a fast food meal and bed, when she spies one of the few coworkers she started with, Darryl, huddling at the bus stop in freezing cold. She briefly considers offering him a ride, but the thought of even that slight delay from getting something to eat and falling into bed is too much to contemplate.

“Fuck Darryl.”

“So I pretend not to see him. I find it hard to explain the needling shame I still feel about this. It’s not a big deal and I’m positive Darryl wouldn’t hold it against me. But I like to think of myself as someone who would offer a nice kid a ride home after a truly shitty day of work. Right now, though, exhaustion has shrunk my circle of empathy to the point that it is hardly big enough for myself. I didn’t know this could happen, and it is not pleasant. I guess I never realized that this might affect more than just my body.”

As she drives away the realization that she is blessed to come from the upper class and won’t ever really know what it feels like to work for most of your life in a job where every second must be accounted for, isolation is deliberate and under the constant threat of being fired for moving too slowly or taking too long of a bathroom break.

“I take one more look at Darryl in my rearview mirror. I could still go back. But in the place I would usually feel empathy, there’s just a shameful, overwhelming relief, and the words, ‘I get to leave.’”

Research

On The Clock is not just about slamming Amazon, call centers, or fast-food restaurants. It is an exposé on how huge corporations are increasingly using technology to drive their employees harder, to squeeze as much work out of them as possible at the lowest possible wage.

It is also a history lesson in Taylorism defined by Merriam-Webster as:

“A factory management system developed in the late 19th century to increase efficiency by evaluating every step in a manufacturing process and breaking down production into specialized repetitive tasks.”

While that sounds benign it is actually a system to eliminate the need for most skills and keep workers in monotonous positions doing the same thing over and over again, day in and day out while justifying paying them so little but expecting them to work at breakneck speed for hours at a time.

“But Taylorism had no ceiling. Its combination of objective-seeming data analysis, specific productivity goals, monitoring, and deskilling was the system factories had been desperate for. By conceiving of workers as numbers in an equation rather than individual humans, Taylor made it possible for companies to expand enormously, employing thousands and even millions of workers without losing control over them.

Taylor’s results could be incredible but left a trail of discontent behind him. Men complained of overwork, exhaustion, and the mind-numbing monotony of this new kind of work.”

Henry Ford, the father of the modern automobile, also gets a few paragraphs and his glowing legacy dims a bit when you realize how he contributed to today’s business model of overworking employees with the lowest compensation possible creating a workplace with high demands but little reward for the efforts of the workers.

Convergys

When you call about a billing issue for a new smartphone contract, dishwasher repair, etc, you will most likely be routed to a huge call center like Convergys in Hickory, North Carolina. Author Emily Guendelsberger worked on the AT&T call center floor where she spent two weeks training to learn how to toggle between several different screens and read scripts but basically be unable to really do anything for anyone who calls in.

Because call center employees do not actually work for AT&T they do not have real access to anyone’s account, cannot issue refunds, or change the minutes of usage allowed on your phone, for example. All they can do is read a script and make notes in the account. While reading the script and typing notes toggling between multiple screens she was expected to remain upbeat, friendly, and apologetic for whatever problem the person was calling in about.

Understandably call center workers are routinely screamed at, cussed at, called really despicable names, and even threatened.

Also, understandably, turnover is incredible. People come and go with breathtaking regularity. Despite the fact that training a new employee takes upwards of two weeks the author muses as to why Convergys doesn’t do more to ensure a better work environment to keep employees instead of constantly replacing them.

Instead, the company monitors how long employees spend on a bathroom break. Taking too long in the bathroom or being a minute or two late back from your break is considered “stealing time from the company.”

“Imagine having to put a code into your phone when you go to the toilet and then have a weekly meeting with your supervisor where you have to justify 1.2 minutes above the average toilet break allocated to you last week.”

While not as physically demanding as working at Amazon, in some ways the author found call center work more damaging because of the mental stress.

“Amazon workers complained about the physical stress of techno-Taylorism. But an alarming number of call-center reps mentioned experiencing mental stress, citing their jobs as the direct cause of intense bouts of depression and anxiety as well as ulcers and other physical effects of stress. I could, unfortunately, fill yet another twenty pages with stories from reps who said their jobs had driven them to seriously consider self-harm or suicide.”

The simple solution would be, it seems, is to just get another job. For those living in Hickory, NC, the jobs are limited and most have gone from one low-paying labor-intensive job to another since the good-paying jobs at the furniture factories were lost to international trade deals like NAFTA years ago.

“The cost of living in Hickory is pretty cheap but a breadwinner here still has to make a minimum of $20 an hour to support a stay-at-home parent and one child. “ (Base pay at Convergys is $10.50 per hour)

The ladies the author is living with while working at the call center both work there as well and have a daughter. They drive 40 minutes each way to a grandparent’s house five days a week because they can’t afford paid childcare even though they both work.

“Welfare made up some of the difference for a few months after McKenna was born but Jess hated feeling like she was sitting around taking handouts. So she decided to go back to a work decision that makes no logical or financial sense.”

McDonald’s

If you have ever wondered about the constant sound of alarms going off at most fast-food restaurants, wonder no more. Every task is timed. Alarms blare constantly throughout each shift to warn workers that they are not working fast enough. No matter how short-staffed or how long the line, at McDonald’s the alarms do not take anything into account, because to reach maximum productivity you must make a milkshake, flip a dozen burgers or reload frozen fries into the fryer in the time allowed or face being written up for going too slow.

The entire work model at the McDonald’s in San Francisco where the author worked is based on only having enough employees so that everyone has to work at maximum efficiency, without pause, no room for mistakes under constant pressure. If 10 could run the kitchen comfortably only five people will be scheduled.

Hostile customers who resent waiting in line, pranksters demanding secret sauce, and a vengeful honey-mustard packet flinging woman are all in a day’s work for the average fast-food employee.

Part of the reason for this is:

“-in November 0f 2014 voters overwhelmingly passed a ballot measure that would gradually raise San Francisco’s minimum wage to $15. San Francisco has universal paid sick leave, and the biggest retail and fast-food companies can’t schedule their San Francisco employees the way companies do most everywhere else. It’s an attempt to disincentivize common practices like (A) employing a large staff of part-timers or temps instead of a smaller staff of full-timers to avoid paying for benefits and (B) scheduling in a way that’s nice and flexible for the company but leaves workers unable to plan their lives more than a couple of days in advance.”

So the take-away is, despite the goodwill of voters passing a law to increase minimum wage large companies go to great lengths to keep profits the same or grow simply by keeping staff to a minimum and expectations at maximum. Scheduling is done by algorithms that predict how much business will come in and the bare number of employees needed to meet it. If one or two employees call in sick, well, those who do show up just have to work that much harder to keep up with demand.

“Understaffing is the new staffing.”

“Exhausted workers and impatient customers tend to create a feedback loop of frustration and negativity that makes for a really miserable day.”

Summary

One of the reasons I consumed this novel eagerly is how much sense it makes about the current labor shortage in this country. While the author’s experiences were all pre-COVID they explain why so many restaurants, call centers, and stores are desperately short of employees.

Many fast food places operate ghost kitchens, offering only delivery or take-out with no in-house dining, have shortened their hours of operation, and are even closed one or two days a week. Despite offering significantly higher starting hourly pay, places like Noodles & Company only get one or two applicants a month and if one actually shows up for an interview it’s a miracle.

Walkthrough any mall or shopping center and you will see “we’re hiring” signs in every storefront. Outrageously long hold times are the norm whenever you call about a billing issue or want to schedule a repair service and you often have to wait weeks for the appointment.

It was predicted that with federal supplemental unemployment relief checks ending in September people would start running back to work in fast food joints, call centers, factories, and warehouses, but that just hasn’t happened. Even with higher wages offered many workers are reluctant to return to the monotony, stress, and anxiety of working for a large corporation under constant duress to work harder, faster, and longer hours, trading their lives for a small paycheck that barely allows for a roof over their head and food on the table.

If you pick up a copy of On The Clock, and I highly recommend you do, don’t skip the footnotes. Lots of juicy stuff tucked in at the bottom of the pages. It might also inspire some compassion when you are feeling impatient waiting for your Big Mac or to dispute a billing issue with your new tablet or smartphone remembering that you are talking to an actual human being, not a robot, who is probably under a tremendous amount of stress to meet unrealistic productivity standards and go home at the end of an exhausting day with little to show for it.

Neale Orinick is a Denver-based writer, wordsmith, and book aficionado who loves red wine and dark chocolate. You can find more about her work at Noted by Neale Orinick dot com

Is technology the problem, though? We can organize work and coordination without Taylorism. See: https://complexitymatters.substack.com/p/s01e02-how-one-man-created-the-single