The Unmasking of Free-Market, Existentialist Wisdom in a Frenzied World

P

Unsplash Photo Credit: Engin Akyurt

With the COVID-19 pandemic now in full bloom, many of us are feeling unsettled, distracted and confused as to what might lie ahead. It’s times like this that we often seek out uncommon perspectives that help to ground us in our rai·son d'ê·tre.

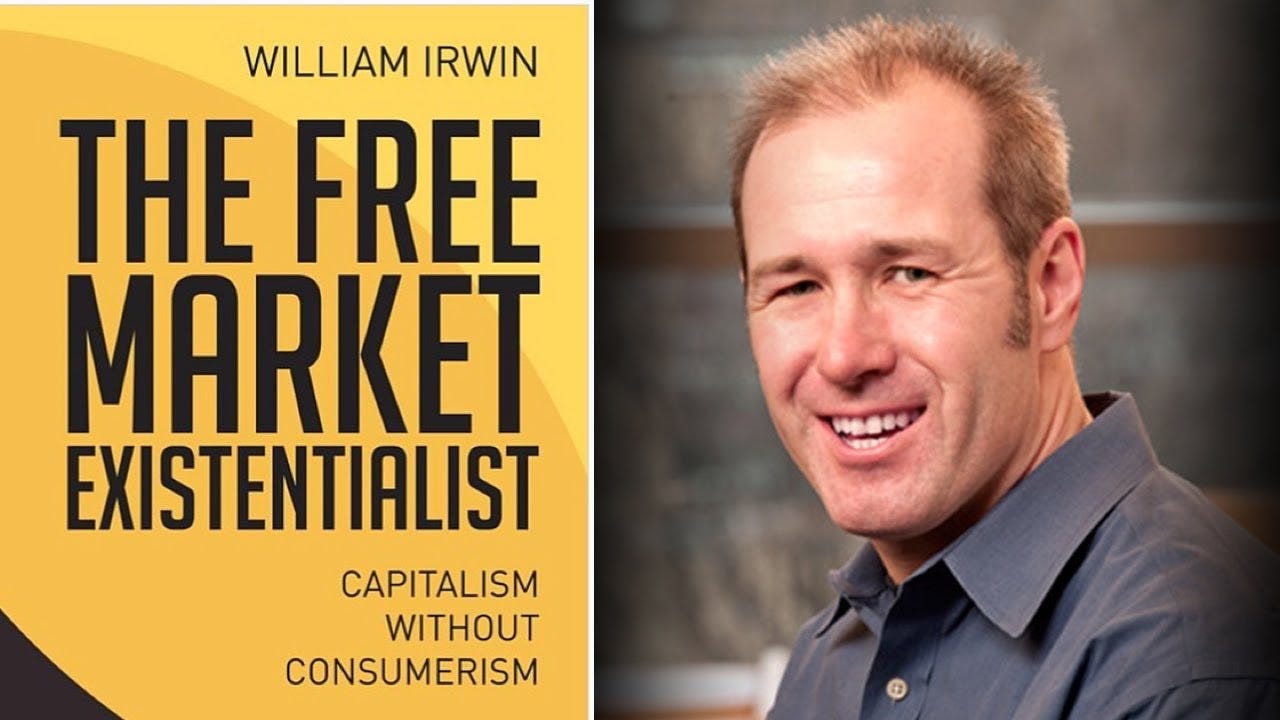

Recently, I reached out to reconnect with William Irwin, someone I’ve featured in a number of articles over the years. A Professor of Philosophy at King's College in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, he is the author of the Free Market Existentialist, a book which argues that capitalism and existentialism are essentially connected at the hip. In it, he asserts that the synthesis of these two doctrines offers a practical model for fostering a truly free-market minimal State that allows people to live in whatever way they please.

What makes this book particularly noteworthy during the times we’re in is Irwin’s existentialist defense of libertarianism, a path of intellectual inquiry that brings together two approaches that traditionally have been viewed as incompatible. Existentialists, notes Irwin, emphasize the importance of subjectively choosing one’s values, a key element in determining one’s meaning in life. Libertarians champion strong property rights and the individual’s prerogative to live in a manner that doesn’t cause harm to others.

It’s this latter point that I have been wrestling with in recent days as cities seek to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus through mandatory “shelter in place” edicts. On the one hand, most infectious control experts agree that these measures are vital to “flattening the curve” on COVID-19, saving countless lives across the world. But as many of us are starting to realize, the constraints being placed on both individuals and the world of commerce could have devastating economic and social consequences on our nation.

And then there’s the issue of what all of this might look like for our individual liberties and freedoms. Ultimately, says Irwin, individualism is the link between existentialism and libertarianism, producing a philosophy that values freedom and a corresponding responsibility.

Opportunities like this to converse with a leading thinker like William Irvin has long been one of the joys of my work as a journalist. Below are a few of his philosophical views that while recorded a few years ago still hold relevance for the unprecedented times we’re in. My hope is that it offers you some useful insight for navigating the cloudy days ahead.

What is the essence of your philosophical leanings?

As with most thinking individuals, Michael, that’s a long story. I would say that I, like a lot of libertarians, didn’t consider myself interested in politics at all until I was well into my 30s. To my mind, politics and political theory were a necessary evil, which I could happily ignore. But as I got older, I realized that I could no longer ignore that reality. So existentialist philosophy — along with social and economic philosophy — became the place I gravitated to.

You have mentioned French philosopher Jean-Paul Satre as someone who has informed your thinking over the years. Tell us a little about that.

Sartre comes from an atheistic perspective that follows my own. The importance he placed on individual freedom and individual responsibility all sounded great to me, that until later on in his career when he embraced Marxism. While I have no issue with people changing their minds and viewpoints the vexing thing about Sartre was the fact that he never acknowledged having changed his views. Oddly, he somehow thought that his previous philosophy of freedom and responsibility dovetailed well with Marxism.

Did his views have any impact on your decision to write Free Market Existentialist?

They did. In many ways, I’ve long admired Sartre’s existentialist philosophy. But frankly, his political turn towards Marxism has always rubbed me the wrong way because it just never seemed to fit in with the rest of his philosophy which emphasized freedom and responsibility. So for quite some time, I had it in mind to try to reconcile existentialism with capitalism and free-market thinking. So during a sabbatical of mine a few years ago, I set this project for myself which is how the book emerged.

In it you connect the dots between existentialism, amoralism, and libertarianism. Please elaborate on this.

Yes, those are the three controversial themes that I stake out in the book and that I then weave together. The first is what you and I have been discussing, making the case that Sartre’s existentialist philosophy is not actually a good fit with Marxism. In the book, I argue that his views are instead a good fit with capitalism; the idea being that if we are free and responsible, capitalism is the economic system best suited for that.

Then there is Amoralism — or what I call moral anti-realism — which embodies the atheistic turn we saw in philosophy quite some time ago, beginning with Nietzsche. With that shift came the belief that somehow the whole world would go to hell in a handbasket. But what we are discovering is that atheists are no better or worse than the average person in terms of how one might judge their actions or behavior.

Finally, from a libertarian point of view, I argue that freedom and responsibility are actually a good thing; that they help the cause of capitalism by serving as sort of a cure for the things that people tend to worry about in a capitalist society.

That seems to comport with the subtitle of your book, “Capitalism Without Consumerism.”

It does. Michael, there’s often this great fear that capitalism is going to turn us all into mindless drone-like consumers. It’s as though we have no free choice in deciding for ourselves how we’re going to live, what we’re going to choose, what we are going to value. Again, I argue that personal freedom and responsibility is the exact message that people living in a capitalistic society need to hear. It’s the notion that one doesn’t need to drive a fancy car or wear certain clothes or things like that. Rather, the assertion is that you can define yourself by your own lifestyle choices versus what the rest of the world thinks.

So how does this philosophy align with your own personal lifestyle choices?

What suits me best is a kind of voluntary simplicity. I don’t indulge in a lot of flash and show. I’d rather have my time and money to spend in other ways that fulfill me more.

In light of the current pandemic, I’m particularly interested in your thoughts on the economic impact of business closures balanced with the need to mitigate the spread of the virus via “shelter in place” orders. Isn’t that a constraint on freedom and personal lifestyle choices?

Yes and I do believe in laws that prohibit risky behavior on the grounds that it may cause harm to others. An example that comes to mind for me is drunk driving. For the moment I'm willing to say that keeping certain businesses open is akin to drunk driving.

Many people are currently re-evaluating what meaningful work means to them. How does your book speak to that?

In the book, I take up existentialism as a remedy for alienation: one of the perceived problems of a capitalistic system. It’s the idea that people are working in jobs that they find meaningless and purposeless. That’s certainly a genuine issue, but one that in my estimation is more tied to an individual rather than to the system. I believe that virtually any job can be exercised to the point where it can be considered a calling if the person adopts the right mindset. We should pursue a chosen line of work, instead of drifting into a life where one’s whole self-esteem is bolstered by ornaments of status like driving a BMW.

That being said, this should not preclude a person from working a job that they find meaningless because they desire enough time and money to pursue other activities that they find meaningful. In the end, these are all tradeoffs for which we have the freedom to take personal responsibility.

What do you see emerging from this self-assessment?

I think our prevailing times are really hard on those who realize in mid-life that they’ve been on the wrong track. We all know people who were told to be an accountant or an engineer, simply because they were good at math when they may have wanted to make music, become an actor, or work with underprivileged children instead. Sadly, so many people have dreams they have shelved because they were told that what they were pursuing wasn’t practical.

So I think there’s greater hope for younger people if they simply give themselves a chance, at least while in their twenties, to pursue what they truly want to do for a living. I always tell students who ask me about this to imagine what they would be doing with their time if they won the lottery and if money were no object. Because it’s really a shame if people don’t give themselves the liberty, particularly in their early years, to pursue something they enjoy. Sure, not everyone is going to succeed as an actor, artist or whatever interests them, but at least they can pursue it with gusto.

I’m curious about your deeper views on risk-taking in life?

There’s no denying that it’s a bit of a leap for most people to try new things. It takes a bold personality, which is why not everyone does it. But there are plenty of stories I can draw on from people I’ve worked with in the past, where the risk was worth it. One that comes to mind is a student of mine who wanted to work for the FBI. Problem was, he was essentially deaf and could only hear with the support of a hearing aid. So the belief was that he wouldn’t pass the FBI medical exam. But guess what? He found a way around that obstacle and is now working for the FBI doing intelligence analysis.

Circling back to a central theme of your books which is Capitalism, can you offer some insight into why that concept is viewed negatively in many circles?

Although I try to avoid the term ‘Capitalism’ as much as I can, ‘Capitalism Without Consumerism’ is the subtitle of my book. Many people, especially on the left, are against capitalism. But if I propose capitalism without consumerism, then suddenly that sounds like a good deal to most people. Except they automatically believe that the intersection between the two is impossible.

But back to the point about word choice and rhetoric. I have the same concern with using the word capitalism, and of course, the word is rooted in Marxism. Sadly, it’s become a disparaging label and a misnomer, a notion that people get rich simply because they’ve hoarded capital, which is not the case. My preference is to address all of this from a property rights perspective. In other words, in owning your own person, you own your own labor and thus should own the fruits of your own labor.

In your book, I was particularly struck by the chapter entitled ‘What’s Mine Is Mine.’ Can you elaborate a bit on your intention in this section?

This chapter of the book provokes readers a bit in that it’s something that most people hate to hear you say. It’s not intended to suggest that you couldn’t or wouldn’t share what you have with others. Rather, the argument is that we should be free to share voluntarily, instead of through coercion. I believe that under a truly free-market system, people would have so much more wealth at their disposal that they would share, and therefore we’d see a significant increase in charitable giving and activity. This is opposed to the sentiment of many people today who feel they have already given enough via tax payments that have, in a sense, been forcibly taken from them.

Still, the thought exists that our world would be uncaring and unfeeling if we’re not taxed in order to take care of people in need. I think the message should be quite the opposite; that people would be more inclined to give and care for others in need if they could make this choice voluntarily.

In closing, please share a final thought about the ultimate aim of your book and why people should read it.

For me, the book offers a message of personal empowerment. In other words, you get to choose how you live your life, and not just in the existential sense. Also, you get to choose how to live your life in terms of how you will spend your money and dispose of your property. That’s the part that has always struck me as missing from existentialism; namely, that individual freedom also has to extend into the economic realm.

An Invitation

Join My Quest To Create a Global Community of 1-Million Authors and Readers By 2030

As a veteran independent journalist and global book ambassador, I strive to provide world-class feature stories on authors and thought leaders who are making a profound difference on our planet. This endeavor is fueled by “Great Books, Great Minds,” a free publication I write and curate each week through the generous encouragement of readers worldwide.

At the crack of dawn each morning, I am up reviewing some of the world’s most compelling reads in order to deliver insightful advice and wisdom to our readers and fans. This comes from my deep passion for books and their role as the “Currency of Connection” for humanity.

So if you are inspired by my quest to create a worldwide community of 1-Million Author and Readers by 2030, then please consider becoming a member supporter of the “Great Books, Great Minds” digital community. In addition to the regular features, subscribers will receive exclusive access to feature interviews and private discussions with some of the world's top authors.

At $6.00 per month (or a discounted annual rate of $60.00), every little bit counts.

Thank you for your consideration. Your support really matters, particularly during these uncertain financial times.

~~

Onward To The Next Chapter,

Diamond (Michael) Scott

Independent Journalist and Global Book Ambassador

Thebookpolymath@gmail.com