Unsplash Photo Credit: Jeffrey Grospe

Thank’s to the wrath of coronavirus, we are mired in the throes of uncertainty. We are in times of uncharted territory.

Like you, I’ve been huddled up at home a ton lately in accordance with Denver’s “stay at home” order.

I’m not going to lie, it is starting to make me bat crazy.

This past weekend, I was reminded of the exhilarating feeling of a long walk.

Nature’s presence. The air. Mindfully putting one foot in front of the other.

Since 2012, walking has been my joie de vivre. That was the year I went car-free, having made the intentional choice of foot power over 4-wheels.

In so many ways, this experience has been life-altering.

So imagine my thrill in stumbling across an article entitled “A Long Walk Can Change Everything” by

. It was music to my ears, or should I say my feetThe article’s very first paragraph immediately captured my attention. She wrote:

“The way we walk right now might feel inhuman — it goes against our evolutionary wiring to avoid connecting with other people. When we see a neighbor, we wave from afar. We give strangers a wide berth. There are no coffee shops to stop at, and no casual errands to run. It can seem like walking just for the sake of walking is not worth the effort”

After reading her wonderful article, I reached out to Antonia to share my experience of crossing paths with scores of people on walking paths and trails these days, all with masks on. On my treks, I was struck by the new normal we are faced with, adorned in masks, at least for the foreseeable future.

What saddens me is how these face coverings serve as a barrier to connecting and acknowledging one other, either through a gregarious smile or silent hello.

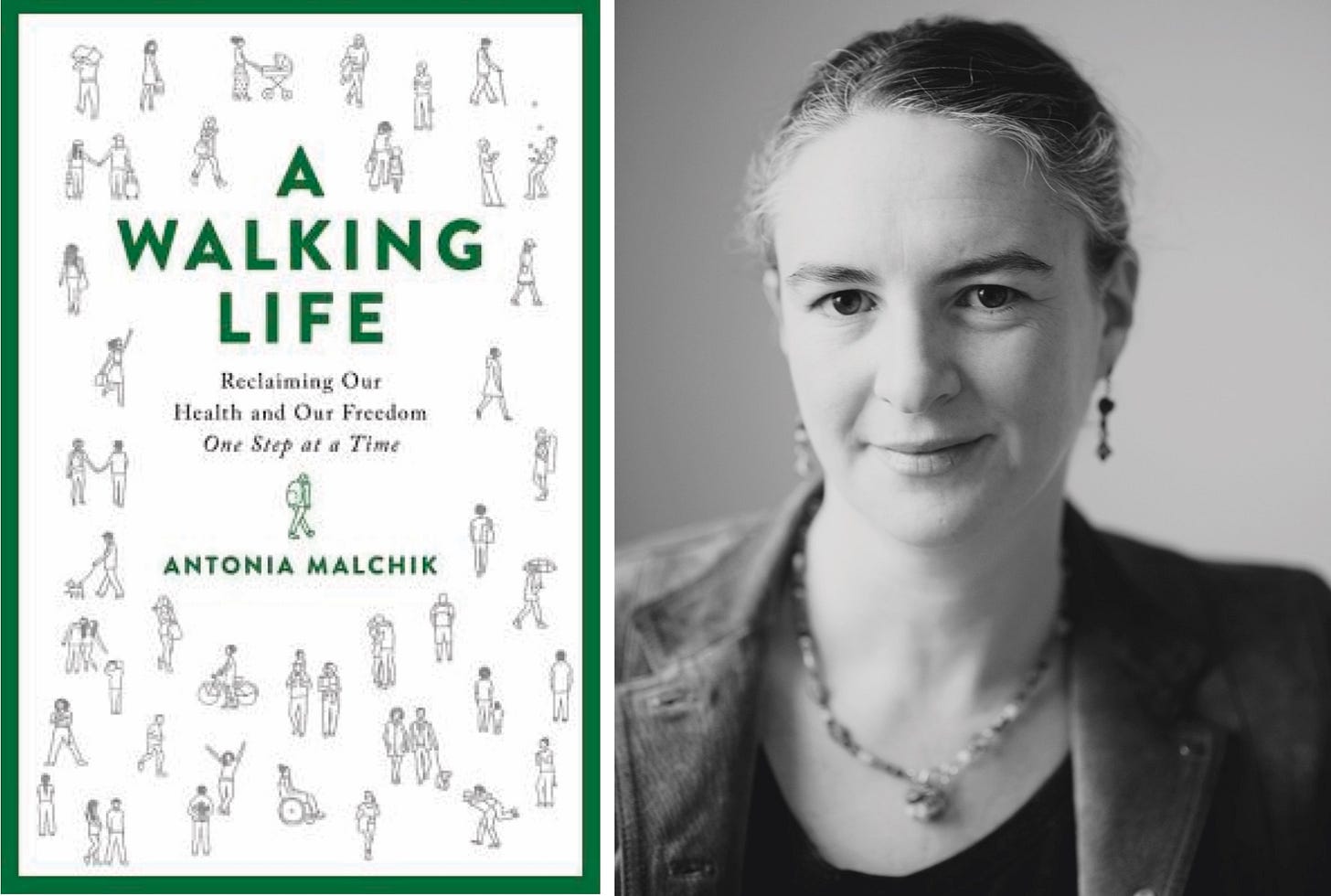

In my dialogue with Antonia, I was also delighted to learn that she’s the author of a book entitled “A Walking Life: Reclaiming Our Health and Our Freedom One Step at a Time.” While I’ve yet to read it, I thought it was worthy of being featured with my global community “Great Books, Great Minds.”

As noted in a description of the book:

Antonia Malchik asks essential questions at the center of humanity's evolution and social structures……..

Who gets to walk, and where? How did we lose the right to walk, and what implications does that have for the strength of our communities, the future of democracy, and the pervasive loneliness of individual lives?

The loss of walking as an individual and a community act has the potential to destroy our deepest spiritual connections, our democratic society, our neighborhoods, and our freedom. But we can change the course of our mobility.

And we need to. Delving into a wealth of science, history, and anecdote, from our deepest origins as hominins to our first steps as babies, to universal design and social infrastructure.

A Walking Life shows exactly how walking is essential, how deeply reliant our brains and bodies are on this simple pedestrian act - and how we can reclaim it.

Antonia was kind and gracious enough to respond to a few interview questions of mine for this feature piece.

Here’s what she had to share:

Tell us a little about you

I was born and raised in Montana, where I currently live. My mother grew up on a wheat and cattle homestead in eastern Montana; my father grew up in Leningrad in the Soviet Union.

When did you first begin to embrace walking?

In 1991, when I was 14, my parents moved us to Moscow in the Soviet Union so they could help start a telecommunications business. My younger sister and I were left on our own after our morning Russian lessons, and we’d wander Moscow for hours. That’s where I learned to love walking in cities.

How did your interest in walking evolve?

I then became interested in researching walking years later when I was living in an unwalkable area of upstate New York, especially after having children and realizing we were completely dependent on the car to get places. The more I looked at our life in upstate New York, the more I began to question what we think of in America as "freedom."

Freedom? That’s interesting. Can you share a bit more about this?

My father grew up under Stalin and was not allowed to speak his opinions or ideas out loud, but he could walk for hours with his friends and they could talk about anything, as long as they could trust one another. Yet if I wanted to take my two small children for a walk I first had to buckle them into car seats and drive several miles.

So walking in your view held a different level of importance here in the U.S.?

Exactly. I lived in a world that was designed for the car, not for human beings, and began to see that much of North America was the same way. At the same time, my babies were becoming toddlers, and since they both received physical therapy through the Early Intervention program, I got to hear from experts about the complexity of walking and the importance of it to children's brain development.

Sounds like it was an eye-opening experience?

It’s interesting that despite decades of research and millions of dollars, we still haven’t produced a robot that can walk on two feet in the same manner we humans do. This is an indication of how mind-bogglingly complex taking even one or two steps is. It's an incredible feature of our unique evolution.

Describe the spark behind your decision to write A Walking Life?

Rather than thinking about what walking meant to people like Thoreau, who gets referenced a lot on this topic, I began to examine what it could mean for a single mom working two jobs; for families living in areas of high crime with decades of disinvestment, crumbling sidewalks, and no parks; for a wheelchair user who has little access to usable sidewalks or decent public transportation; or for a 46-year-old father who commutes an hour each way to a corporate job he hates, who loves his family but feels like his life is missing something essential.

Why do you believe in walking so important?

Walking is crucial to our individual well-being at all levels, from our cardiovascular system and bone density to hippocampus development in children and our ability to handle depression and anxiety. But it's also vital to how we build and maintain communities, and how we connect with one another on every level of being human.

What other purpose does it serve?

The role that bipedal walking has played in our evolution over millions of years, and the development of us as community-oriented creatures, is reflected in our mental health and cognitive capabilities throughout our lives, as well as our physical health. I want people to have access to this because I believe it's central to our humanity.

And your thoughts on how all of this is relevant to the current pandemic crisis?

It’s interesting to me that one of the few opportunities we have right now during quarantines and shutdowns is to look at our cities and towns and realize how much space we give to cars, space that could instead be used for people. It’s also interesting to look at how much time we devote to our commutes and running errands by car. We think cars serve us, but the truth is that we've structured American life and landscapes to serve them.

Can you share a bit more about this?

As I went deeply into the research on walking and walkability, I kept running into themes tied to community, connection, and loneliness. In recent years loneliness has been identified as a public health epidemic for people of all ages, especially the elderly and teenagers, and is being researched and addressed in some cities in the US. Rebuilding walkable communities is key to answering this epidemic.

Loneliness certainly poses a big issue during these quarantines. Your thoughts?

It’s worrisome for sure. Because while technology can connect us in some ways it simply can't make up for physical, face-to-face human contact. While it’s important for us to remain separated in order to prevent the medical system from being overwhelmed, I do believe it’s important for people to familiarize themselves with loneliness and the hard-wired need that humans have to connect with one another.

How can we begin to rebuild those connections when the restrictions start easing?

Right now is a great time to walk with those questions and begin meditating on the answers. You can also look into the work of organizations like GirlTrek, which seeks to get African American women out walking 30 minutes a day for their health, but whose effects spread far into families and communities. It's a model for citizenship that we can all aspire to.

And are there other questions we should be asking ourselves?

Yes, questions like, ‘How can doing something that’s good for your own health and mood also contribute to the community you live in? How can you be a more engaged member of that community? Or what can you do to ensure that it serves everyone who lives there?”

In the end, what are you hoping readers of your book will walk away with?

I'd really love for people to be able to think about what walking has meant or could mean in their own lives. I often hear from people who write to tell me that they haven't finished reading my book because they keep feeling compelled to go for walks. From my point of view, that would represent absolute success.

Any closing thoughts?

Being a human being is a vast, complex thing. It's beautiful, and it's hard. Right now many of us are forced to abandon many of the activities that helped insulate us from that knowledge. Instead of trying to tick through a to-do list, we can use this time to think about what it means to each of us to be human.

Your Invitation

Thank you for joining me here at “Great Books, Great Minds," where your passion for books takes center stage. This endeavor is more than a project; it's a labor of love that's driven by countless hours of research and writing. It's my way of contributing to a world filled with community, connection, and meaningful conversations, all nurtured by the power of literature.

If you've found this digital newsletter to be a source of inspiration and insight, if you relish the opportunity to explore exceptional books alongside remarkable authors and fellow book enthusiasts, then I'd like to extend a special invitation to you.

Join our community as a valued supporting member with a subscription at just $6.00 per month or $60.00 per year. By supporting the world of independent writing you are helping us in our ongoing quest to create compelling experiences between you and the authors that we regularly feature.

Thank you so much for resharing this! It is so good to be reminded of how we first connected, and the incredible power of walking that brought us together--I hope in person someday!

As usual, you provoke thought and reflection. I realize this article is old, but it's also fascinating!